The Arctic environment changes dramatically over the course of a year, transforming from a landscape of ice and snow in the winter to a kaleidoscope of biological activity in the spring and summer. Traditional knowledge passed down through the generations has helped the Inuit of the Arctic make the most of what nature has to offer throughout the seasons.

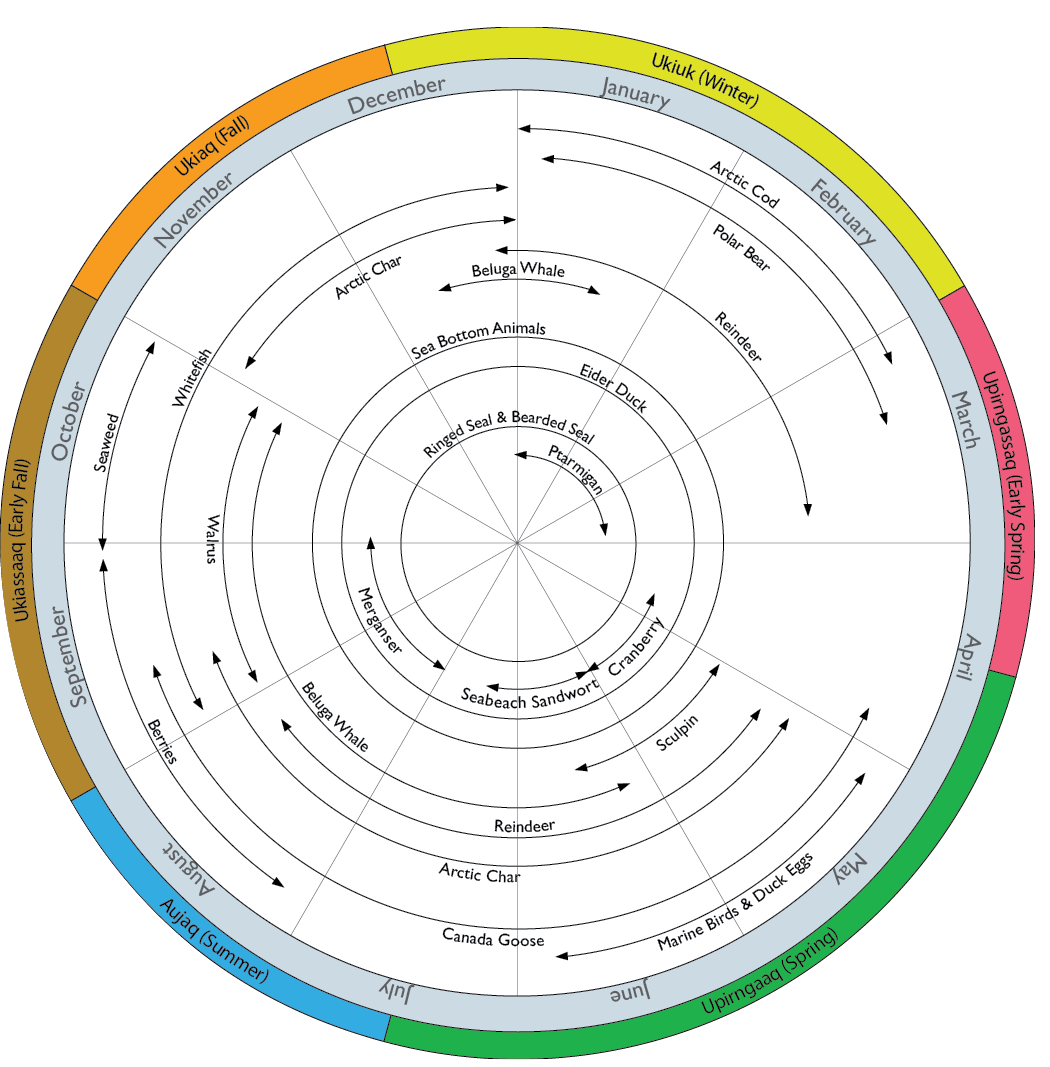

In this activity students will use a food wheel to explore the seasonality of food resource harvesting in Sanikiluaq, an island community in Hudson Bay. Students will then create their own food wheels depicting the seasonal availability of key food items in their own communities, and compare them to the community of Sanikiluaq.

For centuries, the diets of Inuit people in the Arctic have been shaped by seasonal changes in the local environment. In order to survive and thrive in the Arctic climate, people had to develop a keen understanding of seasonal cycles, and a diverse set of skills for successful harvesting of wildlife and plants. They had to know the timing and specific geography of food availability, and adapt to changing and unpredictable conditions year after year. What people ate was governed by the seasons, by their ability to harvest, as well as by cultural and personal preference.

In Northern communities, store-bought foods are extremely expensive and contain far less nutritional and caloric value, gram for gram, than “country foods”, or foods that can be harvested locally. Subsistence harvesting (hunting and gathering food from the local environment) remains a way of life in many Arctic communities today. Modern Inuit apply skills honed over generations to use harvested animals as thoroughly as possible, for food, clothing, tools, art, medicine, and many other uses. Depending on location, animals such as seal, caribou, muskoxen, various whale species, and fish are used to varying degrees by Inuit across the Arctic. For example, the Inuit of Baker Lake call themselves the “caribou people” because of the important role caribou play in their diets. The community of Baker Lake is the only non-coastal community in Nunavut, and so marine wildlife, such as whales and seals, features much less prominently in the local diet.

Fish is dried and preserved over a fire.

In the Belcher Islands of southeast Hudson Bay, Inuit in the community of Sanikiluaq use eider ducks as a major source of food and clothing. Several dietary staples can be found year-round in Hudson Bay, including ringed and bearded seals, common eiders, and sea-bottom animals such as mussels and sea urchins. Among other environmental factors, the presence (or absence!) and quality of sea ice greatly influences what will be available for Inuit to harvest.

Early spring is a particularly difficult time for food resource gathering in the Belcher Islands. Polynyas can freeze over at this time, decreasing the availability of open water in which eider ducks can feed, forcing them to spend more time in open water at the floe edge. The floe edge is where the sea ice attached to land, called landfast ice, meets the moving floe ice of Hudson Bay. Cracks often form between the floe ice and the landfast ice, opening what are called flaw leads. Flaw leads can be used by animals such as seals to access air to breath, and by eider ducks for access to food at the sea floor.

Seals are also more difficult to hunt during the early spring. Seals start making multiple breathing holes in the late fall as the ice develops, and they maintain these holes over the winter by scraping back the ice with their thick nails. However, in the early spring the sea ice is so thick that seals have a hard time keeping their breathing holes open. In the spring months Inuit hunt the seals by waiting at their breathing holes. But as the holes freeze up it becomes more challenging to find both the holes and the seals.

Observations of wildlife and other natural events and human activities tradditionally correspond to the Inuit calendar, which consists of six (or sometimes more) seasons. Each season is characterized by observable environmental conditions relevant to a local area.

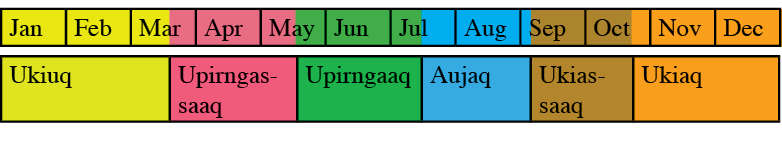

In general, the Inuit seasons consist of Ukiuq (winter), Upirngassaq (early spring), Upirngaq (spring), Aujaq (summer), Ukiassaq (early fall), Ukiaq (fall). A table showing how these Inuit seasons correspond to the commonly known 12-month calendar is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1 - Calendar month to Inuit Season

It is interesting to note how the spelling of the seasons changes based on local dialects, and also how the characteristics of the specific seasons change in different eco-regions throughout the Arctic. This emphasizes how seasonal calendars were understood in a local context and used as tools to understand and live within specific local seasonal dynamics.

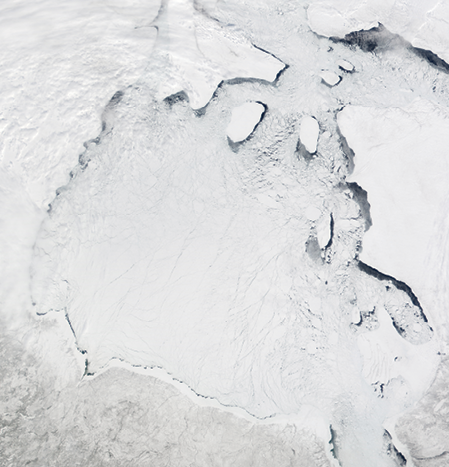

Sea ice covers Hudson Bay. Ice affects what food sources are available to humans and other animals.

Upirngassaq (Early Spring)

- March to early April

- Lengthening daylight hours causes some

snow melt.

- Sea and lake ice is at its thickest and

most extensive.

- Fewer polynyas

- Whitefish and Arctic char overwintering in lakes are not usually harvested at this time.

- Female caribou are generally not harvested during this time because they are calving.

Historically this was often a time of famine as

families reached the end of their winter resources (such as Arctic cod and caribou), and migratory birds had not yet arrived.

The table below shows basic characteristics of the six traditional Inuit seasons for the High Arctic

Region including the communities of Hall Beach, Igloolik, Arctic Bay and Griese Fijord.

How do these seasonal cycles affect people in the Arctic? Understanding the intricate cycles and annual patterns, and being able to adapt harvesting practices around them has played a critical role in the survival and persistence of Arctic peoples.

By creating a seasonal food wheel diagram, we can visualize and understand how different environmental and biological conditions at different times of the year give rise to the diverse local diets characteristic of Inuit communities.

Math

For a graphing activity suitable for Grades 6 to 8, access the Nunavut Wildlife Harvest Summary (See Resources for link). Have the students select a coastal community in the Hudson Bay region: Arviat, Chesterfield Inlet, Coral Harbour, Rankin Inlet, or Whale Cove. Have the students create bar or line graphs showing the monthly harvest of one species (ie. caribou) during one reporting year, much as in the “Food From the Ice” lesson plan. Have the students write a paragraph explaining the line shape/trend. For example, in which month is the largest harvest and, using the knowledge gained in this lesson, what are possible explanations for this peak in the harvest? Additionally, students can find the mean, median and mode of their data set.

Art/Social Studies

For an art project suitable for Grades 6 to 8, students can use cutouts from cooking magazines and grocery store flyers to create seasonal food wheel collages showing the seasonal availability of local food in your community and comparing it to the Hudson Bay region. This project can be completed under a sustainability theme by having the students feature their food wheel collages on posters advertising how to eat locally and seasonally, and then displaying these posters in the school or community. For more information on seasonal harvests in your area, check out the local food guides and Eating by the Seasons recipe book (see Resources).

Home Etc

Have students find a recipe for each season that includes local ingrediants that would be in season. Recipes could be found in cook books, online or by asking family and friends. Have students add photos or drawings to thier recieps and then compile all the reciepes into a local seasonal class cookbook. Optionally have a class potluck where students make and bring some of the dishes from the book. See Great Meals for a Change in the resources section for ideas.

Social Studies/Native Studies

If you are based in the North, invite an elder or knowledgeable person to share traditional knowledge about the six Inuit seasons. If you are not in the North, contact an Aboriginal association or native friendship centre in your area to find someone to share traditional knowledge with your class about and seasonal use of local natural resources.

Nunavut Wildlife

Harvest Summary

www.nwmb.com/en

Download the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board’s 2004 summary of wildlife harvesting, either in full or by community.

Nunavut Wildlife

Management Board Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study

http://www.nwmb.com/en/publications/bowhead-knowledge-study

Local Foods

Want to find out what local foods are seasonally available in your area? Provincial and municipal guides are often online. For some examples:

B.C.

www.getlocalbc.org

Ontario

www.foodland.gov.on.ca/english/availability.html

Quebec

www.trousseals.org/pdf/english/documentsutiles/quebec_seasonal_produce_calendar.pdf

Nova Scotia

http://www.selectnovascotia.ca/recipes

Eating by the Seasons

Recipe book

published by the Halifax-based Ecology Action Centre, with 160 recipes featuring seasonal recipes, a guide to sustainable seafood and finding locally produced food.

www.ecologyaction.ca

Voices from the Bay

Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Inuit and Cree in the Hudson Bay Bioregion. Canadian Arctic Resource Committee and Environmental Committee of the Municipality of Sanikiluaq. (1997)

www.carc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=109&Itemid=171

The examples in italics are possible answers to the disucssion questions.

- How do seasonal changes strengthen the nutritional quality of the diet of Inuit from Sanilikuaq?

Inuit harvest different plants and animals in each season. This dietary diversity allows for a greater opportunity to get a variety of nutrients throughout the seasons.

- What is the advantage of harvesting many different types of animals and plants?

As explored in the Arctic Food Webs lessons, food webs with many connections are usually more resilient. Humans are part of the environment, and we rely on many ecological relationships to sustain us. If Inuit only harvested a few species, and one of those species declined or went locally extinct, this would have very negative consequences for survival. Using a diversity of plants and animals as food resources contributes to human resilience in Inuit communities.

- Which season provides the smallest diversity of food resources? In other

words, in which season is it most difficult to find a variety of food resources?In early spring, the sea ice is at its thickest and greatest extent, and so many traditional foods are not available at this time. For example, polynyas can freeze over, forcing Eider ducks to other locations such as flaw lead areas. Seals may also be harder to find because their breathing holes can freeze over. Furthermore, weathe conditions make long hunting trips more difficult and dangerous.

- How does sea ice impact harvesting and food availability through the seasons?

The presence or absence of sea ice creates conditions that either promote or inhibit the presence of food resources, from phytoplankton on up to polar bears! It also influences where and how people can travel to find these resources. Thin and unpredictable ice conditions are dangerous, so travel by skidoo over the sea ice is restricted to certain seasons. Sea ice is a component of habitat for Arctic species such as polar bears and seals that rely on it for hunting.

- What food resources are harvested in the Arctic year-round? Why are some resources not harvested year round?

As shown on the seasonal foods wheel for the Belcher Islands Inuit, eider ducks, ringed seal, bearded seals, and sea bottom animals are harvested year-round. Eider ducks are found here year-round because of the presence of polynyas and due to the open water at the floe edge. Seals survive year-round because they can maintain their own breathing holes through the winter and spring.

Bottom-feeding animals, including mussels, sea urchins, sea cucumbers, clams, and starfish, which live on the sea floor, can be harvested year-round through cracks in the sea ice or by making holes in the ice. Other species, such as caribou, walrus, and whale, although important, are not harvested year-round because of the difficultly of travelling on the land during the freezing and thawing months, as well as other considerations such as the caribou calving and rutting seasons.

- Why are polynyas and flaw leads important to the food security of the Inuit in the Hudson Bay region, and in other regions?

The open water of the polynyas and ever changing flaw leads support animal populations through the cold winter, when most of the sea is frozen solid. The eider ducks and the seals use the polynyas and flaw leads. As shown on the seasonal food wheel showing the natural resource harvesting of the Belcher Islands Inuit these are important sources of food through the winter months.

Adapted from Voices from the Bay, p.21. This chart was compiled using knowledge of Inuit elders and active hunters. McDonald, Miriam, Lucassie Arragutainaq and Zack Novalinga (compilers). Changes in sea ice, climate and seasonality may have impacted the accuracy of this chart.